Private equity funds allocate the proceeds from investment sales according to a defined hierarchy known as the “distribution waterfall.” Typically, the first tier of this waterfall involves returning “invested capital” to the investors, which generally includes their unreturned capital contributions attributable to realized investments and associated fund expenses such as management fees.

The second tier provides investors with a preferred return or hurdle rate on that capital. If the hurdle return applies, a third tier often follows, commonly referred to as the “catch-up”, which allows the general partner to receive the majority of subsequent distributions until it has received its full carried interest share of the fund’s net profits. Thereafter, any remaining proceeds are split between the investors and the general partner based on the agreed carried interest allocation.

Return of Capital

In contrast to hedge fund investors, who typically retain redemption rights, private equity investors receive liquidity incrementally as the fund exits its investments and distributes the proceeds. Accordingly, private equity funds distribute (rather than reinvest) the proceeds from each sale to return capital to investors over time. As noted earlier, the first tier in most distribution waterfalls is the return of invested capital. The specific definition of capital to be returned before the general partner becomes eligible for carried interest varies across fund agreements. Broadly, funds tend to follow one of three approaches to capital return: (i) deal-by-deal, (ii) realized net gain, or (iii) full aggregation.

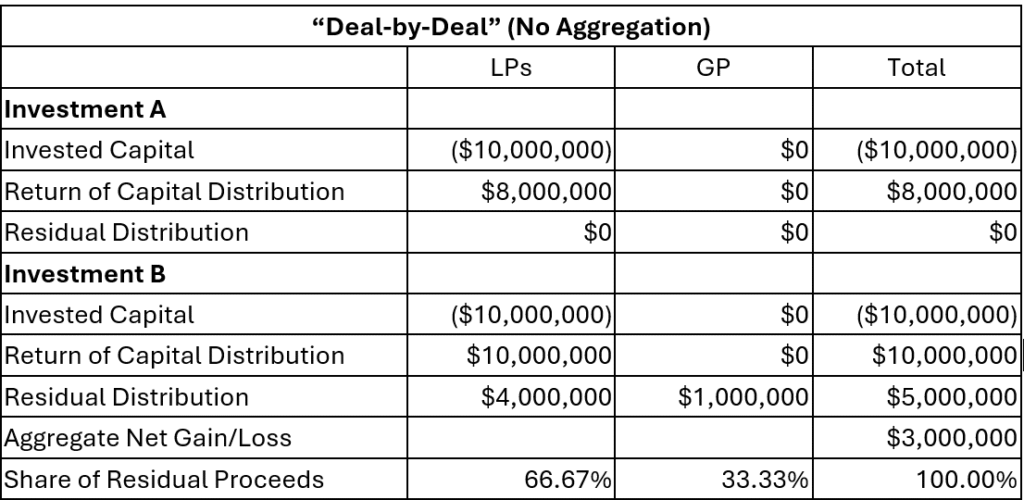

Under a deal-by-deal approach, capital returned to investors typically includes only the amount invested in the specific asset sold, plus any related management fees. If the fund provides for a preferred or hurdle return, this amount may also include the associated return allocable to that investment. Since this method disregards unreturned capital tied to the fund’s remaining portfolio, it may allow the general partner to begin receiving carry distributions before the investors have fully recovered their total invested capital.

Example: Suppose a fund with a “deal-by-deal” distribution waterfall invests in A, B and C at a cost of $10 million each. At the end of the second and third years, the fund sells A for $8 million and B for $15 million (respectively). Assuming a 20% carried interest, the fund would distribute the entire $8 million from the sale of A to the investors as a partial return of their capital invested in A. At the end of the third year, the fund would distribute the first $10 million from the sale of B to the investors to return all of their invested capital in B and the remaining $5 million to the investors and the general partner on an 80/20 basis. Over the first three years, therefore, the general partner would receive $1 million of total distributions, which exceeds 20% of the net $3 million gain from the sale of A and B:

As illustrated in this example, a carried interest that participates only in investment gains is like a call option: the general partner shares in the profits on the gain investments (investment B) without sharing in the losses on the loss investments (investment A). This is why very few funds allow the general partner to participate in investment gains on a deal-by-deal basis. Fewer still follow this paradigm without imposing a “clawback” on the excess distributions at liquidation. If the fund in this example had imposed a clawback, the general partner would have been obligated to restore the $400,000 excess distribution ($1 million – (20% × $3 million)) upon liquidation unless the future sales proceeds from the sale of C were sufficient to reimburse the earlier loss on A.

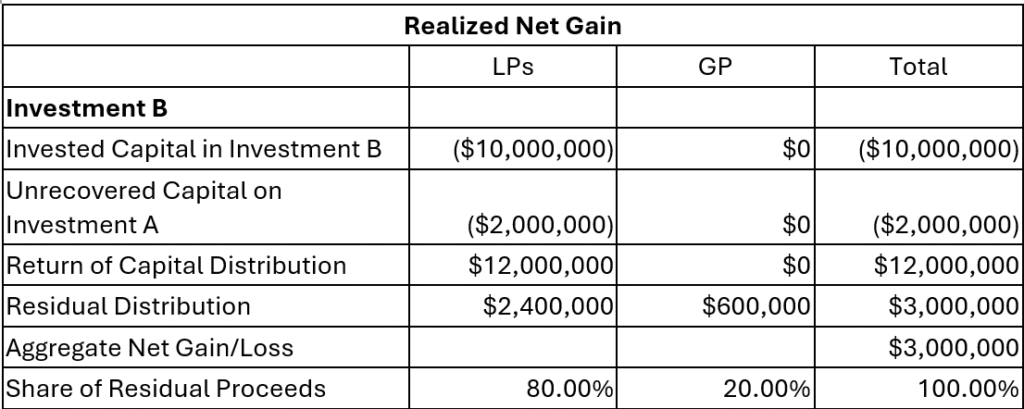

In funds that net realized losses against realized gains, the first tier of the distribution waterfall also reimburses the investors for any unreturned capital on the previously sold investments of the fund. The general partner in a fund that follows this paradigm will not receive a carry distribution until the gain on the current investment exceeds the aggregate net losses on the previously sold investments. If the waterfall includes a preferred return, the general partner will not receive a carry distribution until the gain on the current investment also exceeds the sum of the preferred return on such investment and the accrued but unpaid preferred return on the previously sold investments.

Example: Same facts as in previous example except that the fund aggregates gains and losses. Rather than distributing a full 20% share of the $5 million of gain on the sale of B, therefore, the fund would distribute the first $2 million to the investors to reimburse the loss on A and the remaining $3 million (rather than $5 million) to the investors and the general partner on an 80/20 basis.

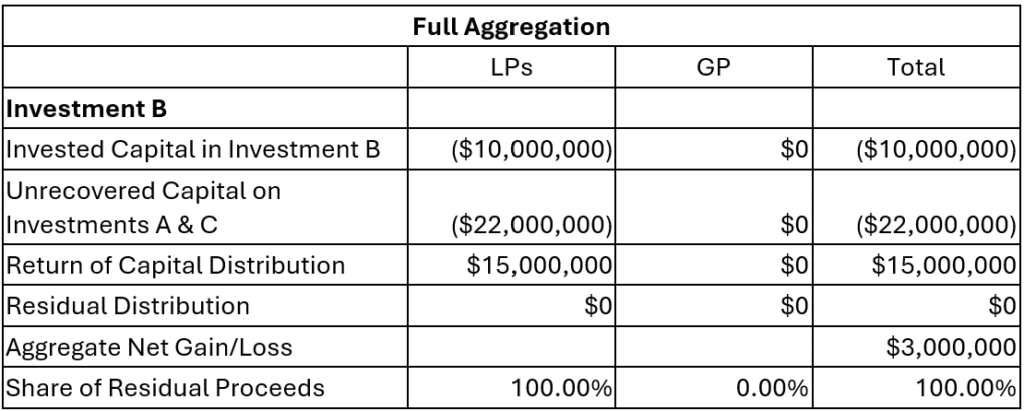

Other funds aggregate all invested capital. In these funds, the investors are entitled to distributions equal to 100% of their invested capital in the first tier of the waterfall, including capital allocable to the unsold investments in the fund. Because the capital allocable to the unsold investments may be substantial, the general partner in these funds is unlikely to receive any carry distributions until late in the life of the fund.

Example: Same facts as the previous example except that the fund distributes proceeds on a fully-aggregated basis. Because the investors still had $22 million of unreturned capital in the fund after the sale of A, they would receive the entire $15 million of proceeds from the sale of B as an additional return of capital distribution.

Preferred vs Hurdle Returns

In a typical private equity fund, the first tier of the waterfall includes a preferred or hurdle return on invested capital. From the general partner’s perspective, a preferred return functions similarly to a return of capital, it represents an amount that must be paid to investors before the GP becomes entitled to any carried interest.

A hurdle return, however, serves a distinct purpose: it subordinates the GP’s carry until investors have received a minimum threshold return. In funds with a hurdle, the total carried interest ultimately payable to the general partner mirrors what it would have been in the absence of a hurdle, assuming the fund achieves the requisite minimum return on capital. To accomplish this, most fund agreements provide for a “catch-up” distribution immediately following satisfaction of the hurdle, allowing the GP to receive the majority of subsequent profits until it has received its full share of the fund’s net gains. When the fund performs well, this catch-up mechanism effectively neutralizes the economic impact of the hurdle on the GP’s overall share of profits.

The Carried Interest

The general partner is entitled to a fixed percentage of the fund’s net gains, a figure that cannot be definitively calculated until the fund has exited all portfolio investments and completed its liquidation. Consequently, regardless of the distribution model applied, the general partner’s right to retain carried interest from earlier distributions remains conditional i.e., it does not fully vest until investors have received 100% of their invested capital plus their share of residual gains (e.g., 80% in a fund with a 20% carry).

Nonetheless, many funds permit the general partner to receive carried interest distributions prior to full investor recovery. This structure rests on the investors’ assumption that the fund’s remaining assets will ultimately generate sufficient proceeds to repay any outstanding capital, including unpaid preferred or hurdle returns. If this assumption proves incorrect, particularly if weaker-performing investments are sold later, the general partner may end up receiving more carry than warranted. The risk of such over-distribution is highest in funds that allow early carry payments without escrowing a portion of those distributions or recognizing unrealized losses on unsold assets.

To address this imbalance and ensure a full aggregation of gains and losses, most fund agreements include a “clawback” provision, requiring the general partner to return excess carried interest if final fund outcomes fall short of the investor priority returns.

Tax Distributions

Regardless of when carried interest is actually distributed, the general partner is taxed annually on its allocable share of the fund’s net income. In successful funds that follow a full-aggregation model, where all invested capital is returned before any carry is distributed, this means the general partner and its members may incur tax liabilities well before receiving any cash distributions. Similar liquidity challenges can arise in funds using a deal-by-deal or realized net gain distribution model, particularly if the general partner is permitted to reinvest sale proceeds rather than distribute them.

To address these timing mismatches between taxable income and cash distributions, nearly all private equity fund agreements include a tax distribution provision. This provision allows the general partner (and in some cases, other partners) to receive cash distributions solely to cover their tax obligations, even if such payments would otherwise violate the standard priority of the distribution waterfall. These tax distributions override the waterfall only to the extent necessary to enable the payment of taxes on current and prior-year allocable gains.

The purpose of the tax distribution mechanism is consistent with other partnership agreements i.e., to mitigate cash flow issues caused by differences in timing between profit allocations and actual distributions. A well-drafted fund agreement will ensure that any tax distribution is offset by prior amounts distributed to that partner, whether for tax or non-tax purposes. This ensures that no partner receives a tax distribution in any year unless their cumulative tax liability exceeds their cumulative prior distributions. In practice, this typically results in tax distributions being made only to the general partner.

In larger funds, tax-exempt and foreign investors who are generally not subject to U.S. tax on most categories of investment income often constitute the majority of the investor base. Despite this, it is rare for funds to exclude these investors from the tax distribution calculation. Typical tax distribution provisions assume the following:

- All investors are subject to U.S. federal income tax at the highest applicable marginal rate;

- All investors are subject to the highest possible state and local tax rates (e.g., those applicable in New York City or California);

- Investors do not have losses or deductions from other sources to offset their tax liability.

Additionally, a robust provision will compute each partner’s assumed tax liability on a cumulative basis. Under this approach, a partner is entitled to a tax distribution equal to the product of the applicable tax rate and the excess of cumulative taxable income allocated over cumulative prior distributions. Thus, a partner who has not received any prior distributions will only qualify for a tax distribution if their cumulative share of income exceeds their cumulative share of losses across all prior tax years.

This article is a part of Private Equity series by Small World Business Advisors LLC and is intended to give a generic overview of the operational mechanisms of a typical private equity fund. Nothing herein constitutes tax or legal advice. For more information, feel free to reach us at [email protected]

Copyright 2025 Small World Business Advisors LLC www.swbadvisors.com